I’ve been reading the book of Job with my literature students recently, and we all agree that we wouldn’t want to claim Job’s comforters for ourselves. They weren’t very comforting. Sure, when Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar first arrived, they grieved with calamity Job silently—but once they opened their mouths, their apparent support for Job deteriorated into accusations. Instead of assuming their upright and formerly rich-in-all-things friend was being attacked by Satan because he was upright and choosing to serve God, they joined in the attack, saying: You must have done some sin! Your children must have sinned! This sort of suffering just doesn’t happen to good people!

I believe they attacked Job because they were afraid. You see, if their righteous friend could do everything right and still suffer, then it could happen to them as well. And they probably weren’t as righteous as Job.

I find myself in a similar situation with my mother.

As I mentioned in a couple previous posts (“Mom for a week” and “Mom’s move to memory care”), my mother has severe dementia. My mom, like Job, lived right. She loved God, her family, and others. She lived to learn and delighted in new knowledge. She was always reading and writing and reflecting. If finances and time had allowed, she probably would have been a perpetual student. She took joy in God’s creation. She loved spending time with family and friends and was the perfect partner for field trips and explorations. She noticed things. She asked questions. She fully embraced every opportunity to learn more. How could a brain that active go bad?

Maybe she could have exercised more and drank more water. Maybe she was too sedentary. Maybe she drank too much coffee. Maybe vinegar wasn’t the cure-all she believed it to be. Maybe it was …. Maybe it was…

Like Job’s friends, I’d like to find that my mother did something that caused the onset of this disease—or failed to do something that might have prevented it. Because then I might have some control over my own future…

Like Job’s friends, I have this niggling sense that “it could happen to me.”

Like Job’s friends, I am afraid.

Every time I forget to do something or forget to bring something. Every time I carefully put something away—only to find I’ve hidden it from myself. Every time I forget a name or can’t find the right word… I fear.

I am very much like my mother—and I’ve always counted that a blessing. Until now. I have no true reason to worry. No doctor has said my mother’s condition is hereditary. But if it could happen to my mother, it could happen to me.

My sister is having that same niggling worry.

When we were filling out the eight-page questionnaire on my mother’s behalf upon her entrance to the assisted living memory care facility (responding to such prompts as “favorite food,” “favorite music,” “favorite people,” “favorite activities,” “favorite memories,” etc.), my sister said she was going to make a copy so she could fill it out in advance for herself while she still could. I returned home from my trip to move my mother and simply told my husband, “If I lose my mind, I am letting you know right now that you can put me in a place like that.”

I think it’s OK to plan ahead for the possibility—a little. Letting my children know what to do should my fear be realized is a good thing. (I sure hope they read my blog.) My first husband, for example, told me that if he died before I did he wanted to be buried where I was, as opposed to being buried where he had spent his childhood. He also said that he thought I should remarry. I thought he was crazy and morbid, but when he died just weeks later unexpectedly, I was so comforted in knowing his wishes regarding burial. A few years later, when I was ready to marry again, I was comforted to know that he felt I should.

Job’s friends feared suffering and so spoke incorrectly. They espoused “Retribution Theology,” which suggests that “if you are suffering, you must have sinned.” Job himself just walked through the suffering (only figuratively; he mostly sat in ashes). He questioned God, but he understood that “the Lord gives and the Lord takes away. Blessed be the name of the Lord” (Job 1:21). He didn’t assume he had committed some sin because he was suffering. He continued to trust God while looking for answers. By looking, I mean, he asked questions. And asked. And asked. Chapters of asking, actually, but I can sum it up: He asked God the equivalent of “why me?”

After 37 chapters of tragedy and the tragedy of friends misleading friends, and Job begging to understand, God speaks to Job. He shows up like a storm, but His voice begins to ask Job questions—all along the lines of “Where were you when I created the world?” He never answers Job’s “why?” Instead, He answers by showing Himself.

Despite my years of teaching Job as literature to my high school students, I never felt satisfied with God’s, to me, non-answer or with Job’s apparent satisfaction with it. Until today.

Last week during my lunch duty, I was speaking with one of my seniors about the book of Job and the fact that God never really answers Job’s question. This student told me that his youth pastor had been speaking on that very topic—why God doesn’t fully answer our question of “why?” So I asked this youth pastor to come address my English classes. For the first time, I understand why Job was satisfied with God’s non-answer.

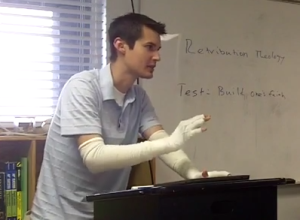

Let me try to outline what youth minister Asa Walker said in class (although you should check out the video recording of one of my classes yesterday for the full exposition—it is great!).

The story of Job begins with an encounter between God and Satan. What was Satan’s role in all this? My intelligent literature students immediately indicated that Satan was the antagonist to Job, the protagonist. Asa, however, suggested that Satan was merely a pawn in God’s immense plan; God, the true protagonist, used Satan to test Job. (Look at Job 1; God is the one who initiates the conversation about Job.) The purpose of the test (actually, any test from God) was to build faith. Job’s saga not only built his faith but also the faith of the rest of us who have heard his story.

How? Job lost everything, his riches, his children, his health. Though Job is considered one of the Wisdom Books in the Bible (which includes Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Song of Solomon, and Ecclesiastes in the Protestant canon), its message is clearly that human wisdom fails. Job’s wise friends—and Job himself—could not determine why Job was suffering these losses. God shows up and never gives the answer—yet Job is satisfied. Why?

Asa used the example of all the arguments he had for remaining single which he wrote in large letters on the white board:

- He likes his freedom.

- He barely has enough money to spend on himself; he wouldn’t want to have to cover someone else’s expenses too.

- He is too young.

- He would have to find a woman who shares his high demand for coffee.

Then he pointed to me, the only married person in the class, to complete his example.

“How many of these arguments did you consider when you got married?” Asa asked me.

“Actually, none of them mattered once I met Steve,” I responded.

“Exactly,” Asa said, as he rewrote the arguments much smaller and then wrote the word LOVE in very large capital letters beneath them. “That’s because it suddenly became personal. All those little questions and arguments you once had no longer mattered in the presence of your husband.”

That is what happened to Job. God showed up. God showed Himself, and it became personal to Job. The questions didn’t go away, Asa said, they just shrank in light of who God was, as evidenced in Job’s own words:

“My ears had heard of you

but now my eyes have seen you.

Therefore I despise myself

and repent in dust and ashes” (Job 42:5-6).

God showed up. Job was satisfied. But God still didn’t answer why. Why?

Because faith isn’t faith if you have all the answers. Dictonary.com defines faith in this way:

“1. confidence or trust in a person or thing;

2. belief that is not based on proof.“

Like Job, I am satisfied.

2 thoughts on “No longer worrying that “it could happen to me”…”